Finance Minister Bill Morneau unveiled the government’s 168-page fiscal “snapshot”, the first formal economic update since the emergence of COVID-19.

Here are the numbers: the federal deficit is projected to be $343.2 billion in 2020-21, which is more than a 1,000% increase over the $28.1 billion deficit projected before the pandemic and the biggest deficit since WWII. The ballooning deficit will push the federal government’s total debt level to $1.2 trillion by March 2021, a number never before seen in Canada. Due to historically low interest rates, the carrying charges on the much, much bigger liabilities are nonetheless expected to be $4.3 billion lower this year compared to those forecasted in the 2019 Economic and Fiscal Update. The deficit comes, of course, from the government’s more than $200 billion in direct emergency spending (the most direct fiscal support of any G7 nation), but also due to forgone returns: the government is projected to lose $81.3 billion in revenue, including a $40.8 billion drop in income tax. The federal debt-to-GDP ratio is expected to rise to 49% in 2020-21, up from 31% in 2019-20 – in part due to increased debt, but also from a 6.8% shrinking of the GDP. This is still a significantly lower ratio than during WWII: between 1942-1945, the federal debt-to-GDP ratio was more than 100%.

Parliamentary Budget Officer Yves Giroux called this snapshot “scary”, “disappointing”, and “unsettling.”

These numbers are big, no doubt, but how accurate are they? Provided COVID-19 remains under control, the federal deficit may not hit $343.2 billion – instead, $343.2 billion is the number the government is confident they can stay within. But, what if there is a resurgence of the virus, requiring new lockdowns and new support measures? The snapshot does not pretend we are through the pandemic, instead acknowledging “the potential for a second wave looms.” Another worry that the snapshot recognizes is disrupted supply chains, saying “supply chain disruptions remain a vulnerability given Canada’s dependence on international trade” and “supply chain reconfiguration is also likely.”

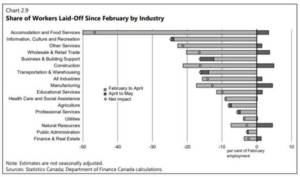

Between February and April, 5.5 million Canadians (1/3 of the entire workforce) either lost their jobs or saw their work hours significantly reduced. As expected, a significant majority of these losses came in the accommodation and food services sector, which is also the sector that remains hardest hit:

What is not included in these charts, however, is the per cent of GDP each industry contributes. In 2017, for example, real estate accounted for 13% of Canada’s GDP, manufacturing 10%, construction 7%, and agriculture 1.5%.

As the government looks to get workers back to work, the Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy will soon be amended and extended to “stimulate rehiring, provide support to businesses during reopening and help them adapt to the new normal.” More money will be injected into the program: today’s release puts the CEWS’ cost at $82.3 billion, up from the $45 billion figure given to Parliament in late June. So far, the program has paid out $18 billion to just over a quarter-million employers.

Prime Minister Trudeau held a press conference ahead of Minister Morneau’s tabling of the fiscal update, where he framed the snapshot as a document that “measures the cost of helping Canadians,” argued that “the cost of doing nothing would be far more,” and said – more than once – “we took on debt so Canadians wouldn’t have to.” Of course, it’s taxpayers who pay to service that debt, even if we don’t pay it off in our lifetime. Canada still hasn’t, for example, paid off our WWII debts.

It was clear that the Prime Minister and his team view the large deficit as an inevitable product of an unprecedented situation; and with nearly 11 million Canadians receiving either the Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy or the Canada Emergency Response Benefit, the position is not unfounded.

The fiscal snapshot, being a status report as opposed to a formal budget, will not be voted on in the House of Commons. This means the minority-positioned Liberal Party does not have to collect the support of another party to maintain the government. It also means that the election-adverse opposition parties are likely to be more critical of the snapshot than they would be if faced with the choice of supporting the document or potentially heading to the polls. Only Elizabeth May of the Green Party voiced support, saying “we are in a pandemic. This spending is essential.”

So, what’s next? It is clear the government has no plans for austerity anytime soon. And, when asked if he has plans to raise taxes to help cover the costs, the Finance Minister said “the answer is a clear no.” Instead, the government re-iterated that borrowing costs are low and will take comfort in the fact that, even at 49%, its 2020-21 federal debt-to-GDP ratio will be the lowest amongst G7 nations, with France, US, Italy and Japan all projected to come in at over 100%. It is not clear, however, what will happen when interest rates go up.

If these insights are helpful to your business, email mcmillan.vantage@mcmillanvantage.com to be added to our daily(ish) updates. Since COVID-19 started, the team has been delivering business and political update to clients and friends of the firm and would be happy to include you on our distribution list.